Retirees Need $130,000 Just to Cover Health Care, Study Finds

Out-of-pocket cost estimates that had held steady have now hit a record high.

Ben Steverman

August 16, 2016 — 6:00 AM EDT -

Today's 65-year-olds can expect to spend an average of $130,000 on health care during their retirement, from premiums to co-payments to eyeglasses, according to new estimates.

The average single 65-year-old woman can expect to need $135,000 to spend on health care in retirement, while a man will spend $125,000, according to estimates from Fidelity Investments. (The difference is because the woman is expected to live longer—an additional 22 years, vs. 20 years more for the man.)

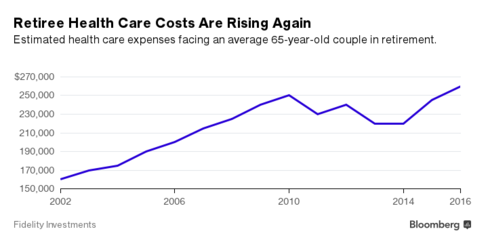

Every year, Fidelity estimates how much it will cost for today's average 65-year-olds to cover health-care expenses for the rest of their lives if they retire now. For a while, it looked as if health care costs were holding steady, but Fidelity this year says couples need to set aside a record $260,000 for Medicare premiums and all other out-of-pocket medical costs—up 6 percent from last year and 18 percent from 2014.

Prime culprits in accelerating health expenses are prescription drugs, especially high-priced specialty drugs, Fidelity says. And as the economy recovers, retirees are using more health care, driving up costs.

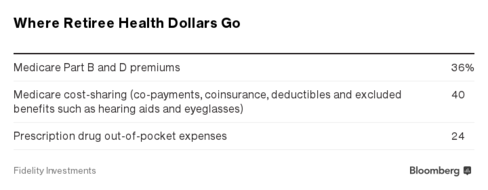

Fidelity's estimates, based on an analysis of Medicare's claims database and trends in survey data, assume that retirees are eligible for Medicare and try to capture all the costs it doesn't cover—including premiums, co-payments, and things Medicare doesn't pay for, such as hearing and vision exams. But the estimates are only averages, and people's costs can vary widely, according to where they live and how healthy they are.

The estimates also don't include long-term care, the sometimes-astronomical costs of home health care or nursing homes that aren't covered by Medicare. Long-term care insurance is available but expensive; although premiums vary greatly, Fidelity estimated that a retired couple would need to pay an additional $130,000 for a policy offering an inflation-adjusted $8,000 per month for long-term care over three years. (It did not examine the cost of a policy for a single person.)

Such insurance offers protection against expenses so huge that they can bankrupt even upper-middle-class retirees, forcing them to spend their assets and go on Medicaid, the insurance program for low-income Americans—which, unlike Medicare, does cover long-term care. Still, long-term care insurance isn't the right option for everyone, cautioned Adam Stavisky, senior vice president of benefits consulting at Fidelity. Some retirees simply can't afford such high premiums, while wealthier retirees might be better off setting aside money for long-term care expenses, in case they arise.

For many Americans, $260,000 may seem an impossible amount to save on top of other retirement expenses, but financial planners say several strategies can help.

First, get the right Medicare supplemental insurance policies. The program is complicated, and retirees may need help from an expert or an organization such as AARP to get it right. "It is astonishing how little people know and how confused they are on this subject," said Frank Boucher, a financial planner in Reston, Va. "Having the right combination of Medicare and a good supplemental policy should cover most health-care costs."

Second, save for health care in a tax-efficient way. If your employer provides a high-deductible health insurance policy, you're eligible for a health savings account. Workers can contribute to HSAs with pre-tax money, providing an immediate tax break, and let the money compound over many years. Any withdrawals used for health care aren't taxed. Even those without HSAs can deduct medical expenses on their taxes if the costs add up to more than 10 percent of their adjusted gross incomes. (For taxpayers 65 and over, the threshold this year is 7.5 percent.)

Third, consider creative strategies to maximize income late in life, when health-care costs tend to rise. By waiting until they're 70 to take Social Security benefits, retirees reap bigger benefits—76 percent higher than if they had taken them at age 62. No safe investments provide that kind of return these days, said Steven Medland of TABR Capital Management, and "those higher benefits last for the rest of the client's life, even if they live until age 110."

Another strategy is a longevity annuity, an insurance policy that provides an income stream that begins only once retirees reach age 80 or 85. Because many people don't live that long, longevity insurance is far cheaper than other kinds of annuities. "A person can make their retirement nest egg go much further," says Barbara Camaglia, the president of Legacy Financial Advisors in Beachwood, Ohio. Retirees can then spend more freely early in retirement, knowing they're guaranteed to get a regular annuity check in their final years.